Heinz Ketchup: The Taste Loved ‘Round the World

February 11, 2015

Johnny Angel

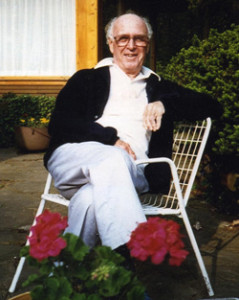

February 11, 2015 Dahlen K. Ritchey was an architectural genius. His kind heart and creative vision helped form quite a few iconic buildings around the Pittsburgh area. Dahl was known as a kind and caring man to all who crossed paths with him. He was loved by his staff. Despite his talent and skill he remained a humble man. He treated all people the same despite their social class.

Dahlen K. Ritchey was an architectural genius. His kind heart and creative vision helped form quite a few iconic buildings around the Pittsburgh area. Dahl was known as a kind and caring man to all who crossed paths with him. He was loved by his staff. Despite his talent and skill he remained a humble man. He treated all people the same despite their social class.

Early Years

Dahlen K. Ritchey was born January 31, 1910. Him and his sister, Virginia, grew up on Parkview Avenue in Oakland with parents Charles and Anne. Their father was employed at J&L Steel.

Parkview Avenue was in close proximity to Forbes Field. Dahl often worked as an usher there. Additionally, many Pittsburgh Pirates chose to make their homes nearby. Dahl’s neighbors included players like Max Carey and Carson Bigbee. He was childhood friends with their children. This was a large reason why Dahl had a lifelong love of baseball. That would serve him well in later years.

Dahl graduated from Schenley High School in 1928. After that he studied architecture at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. Today it is known as the Institute as Carnegie Mellon University (CMU). Dahl got his bachelors and graduated first in his class. While attending school Dahl befriended James Mitchell. James was originally Dmitri Michiel and he was born in Greece.

New Beginnings

Dahl and James went on to graduate with their Masters degrees. Dahl again was first in his class from Harvard. They each won a fellowship to study European architecture. This enabled Dahl and James to travel throughout Europe. While there they studied and sketching the architecture they encountered there. Dahl continued studying and sketching throughout his life. His own home often reflected his love of drawing through his artwork gracing the walls.

Edgar Kaufmann met Dahl when he was hired by the Kaufmann’s Department Store to design their window and furniture displays. Dahl only stayed with the Kaufmann’s Department Store for a year. Dahl and Edgar became lifetime friends in that short year.

In 1938 Dahl and his friend James Mitchell set up an office together. The office was located in the Harvard-Yale-Princeton Club courtyard. By this time they had both earned the right to be called registered architects. Times were lean and both taught classes to help raise the money needed to pay the rent on their office.

Bradford Woods Home

Dahl’s talents could have taken him anywhere but he chose to make Pittsburgh his home. Dahl married and build a life in the northern suburbs of Pittsburgh. Bradford Woods was an area where the city folks typically built their summer cottages. Dahl and his wife, Kay, decided to build a house on a wooded piece of property there. At that time, Bradford Woods did not have a large year-round population.

The foundation of the house was started on December 6, 1941. The attack on Pearl Harbor occurred the day after work on the foundation began. Dahl and Kay signed up to help with the war effort causing the housework to be put on. Dahl enlisted with the Navy and served on the USS Saratoga. Kay did decoding work during the war. The home was not finished until 1950.

Dahl drew up a new design for his Bradford Woods home while serving on the Saratoga. However when he returned building the house was not an easy project. Materials were hard to come by after the war. Additionally, the lack of electricity meant that all of the materials had to be cut by hand. Today, his house is still tucked down a beautiful wooded drive. Unless you knew it was there you would pass right by.

Dahl and James Mitchell established an architectural firm after the war in 1946. They named it Mitchell & Ritchey. The following year at Edgar Kaufmann’s 75th birthday he asked Mitchell & Ritchey for a report. This report would be a projection of what that envisioned for Pittsburgh 75 years from then. The document, entitled “Pittsburgh in Progress” showed their vision of modern Pittsburgh. Some of the buildings they envisioned in their report were actually built many years later.

Mellon Square

William “Fritz” Sippel joined Mitchell & Ritchey’s firm. He was an up and coming architect as well as a WWII veteran. Their firm was growing and as it did so too did their projects. One of their most important opportunities came 1949. Wallace Richards of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development walked into their office on a fateful Friday afternoon.

The Allegheny Conference had powerful connections such as the Mellon family and Mayor David L. Lawrence. Architectural assignments were usually sealed with a handshake at the private clubs. Often by reputation based on previous projects. Dahl and Jim did not walk in those influential circles. This opportunity while they were starting out was not to be passed up.

The young architects were given a verbal picture by Richards of what would come to be known as Mellon Square. This vision originated with Richard King Mellon. Drawings were needed only four days later. The young men spent the weekend studying and walking the 1.37 acre block in the heart of the city. They worked diligently until they were satisfied with their plans. Their drawings were well received and they were awarded the job. Worked in conjunction with the landscape architectural firm Simonds & Simonds they designed an oasis.

Ground was broken on Mellon Square in 1953. It was opened in 1955. The reviews were terrific and Mellon Square was a success. At the time, the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) was threatening to move to New York City. They were persuaded by Richard King Mellon to stay in Pittsburgh and build beside Mellon Square. Additionally, the U.S. Steel Building was built close by.

This modern square gave many Pittsburghers a pleasant break in their hectic work and school schedules. It was built over a parking garage which could accommodate 1,000 vehicles. It brought with it both style and beauty as it incorporated fountains, gardens, and seating.

Mellon Square’s green roof was well ahead of modern greening initiatives. Over the years, lunchtime concerts have been held to the delight of those who happened by. Today’s visitors know little of how important this park was to its young designers. This was just the first of many architectural adventures for Mitchell & Ritchey’s firm. In 1985, thirty years after construction, Mellon Square was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

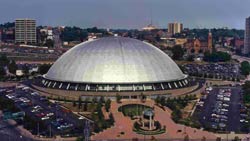

Civic Arena

It was through Edgar Kaufmann that the firm of Mitchell & Ritchey got involved in designing the Civic Arena. Kaufmann personally donated the sum of one million dollars to make the it a reality. He loved the Civic Light Opera and wanted this new arena to be their summer home. Kaufmann recognized that it was not feasible for this building to be in use only during a single season. He sought out another influential Pittsburgher, John Harris, to become involved with the project.

Harris was the owner of the ice hockey team, the Pittsburgh Hornets, and the Ice Capades. Both Kaufmann and Harris were demanding of the architects. Edgar wanted the performers and audience to be outside when the weather was nice. However he wanted to have a roof over the audience and performers if the weather turned disagreeable. Harris insisted that every single seat have a constant view of the puck on the ice. The challenges were many, but Mitchell & Ritchey proved to be up to the task.

They designed a giant dome roof to ensure an unobstructed view from each seat in the house. The roof was designed to have six moveable and two stationary stainless steel leaves. Each made up of four acres of metal, and the moveable ones could retract at the touch of a button in 2.5 minutes. The design of this new structure was truly revolutionary. At this time Pittsburgh was attracting world-wide attention for its new urban rebirth. This innovative design was a very important addition to the city.

The Civic Arena debuted with the Ice Capades on September 19, 1961. Unfortunately, incorporating Kaufmann and Harris’s ideas proved to not be perfect. The acoustics were less than ideal when the roof was open. The wind, even a shallow breeze, would blow music sheets from musician’s stands. Additionally, scenery and props from their designated spots would be moved around. Despite the problems, the Civic Arena would go on to host many famous artists, including Frank Sinatra, The Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead, and Garth Brooks.

Edgar Kaufmann did not live to see the Arena’s completion. While alive he watched each step of construction from his apartment on the top floor of the William Penn Hotel. The Civic Arena was a project that was always dear to Dahl’s heart. In 1957, during the construction, Dahl’s partner James decided to move to Connecticut.

A New Partnership

The rapid growth of enrollment at the Pittsburgh universities presented many opportunities for architects. Dahl designed Allegheny Center For the North Side of Pittsburgh. It was a shopping mall, parking garage, professional offices, town homes and apartments all in one large complex. The Center opened in 1966.

The rapid growth of enrollment at the Pittsburgh universities presented many opportunities for architects. Dahl designed Allegheny Center For the North Side of Pittsburgh. It was a shopping mall, parking garage, professional offices, town homes and apartments all in one large complex. The Center opened in 1966.

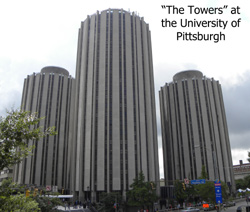

Dahl was also involved in designing buildings for the University of Pittsburgh (Tower Dormitories and Trees Hall) and his alma mater, Carnegie Tech (Donner Hall, Wean Hall and Cyert Hall).

In 1959 Dahl formed a partnership with Russel O. Deeter. Deeter was very involved in university architecture in the city of Pittsburgh. At first the firm was known as Deeter & Ritchey. However, by 1964 it had become Deeter, Ritchey and Sippel Associates. It had offices located in Four Gateway Center.

Dahl knew that to make it really big in the architectural world he should move to New York. This lifelong Pittsburgher choose to stay and still had a very successful career. The size of Deeter, Ritchey and Sippel Associates fluctuated over the years. At one time 83 people were employed there.

Three Rivers Stadium

In 1958 Dahl was approached with the idea for a new stadium. Dahl had a great vision for Three Rivers Stadium. The design Dahl wanted was very much like the present day PNC Park. It would open to the river and city skyline with many movable seats. Also Dahl would have preferred having two stadiums instead of just one for football and baseball. Unfortunately, long delays, political entanglements and construction costs rose with inflation. It was decided that the stadium Dahl originally designed would cost too much to build.

Dahl was sent back to the drawing board. He looked at the Three Rivers Stadium project as both his greatest professional challenge and his greatest disappointment. He thoroughly enjoyed his time working on the projects with Art Rooney Sr. There were many times both men would climb up a ladder during the construction to make sure all the details were being taken care of.

Dahl was sent back to the drawing board. He looked at the Three Rivers Stadium project as both his greatest professional challenge and his greatest disappointment. He thoroughly enjoyed his time working on the projects with Art Rooney Sr. There were many times both men would climb up a ladder during the construction to make sure all the details were being taken care of.

Three Rivers Stadium was completed in 1970. In 2001 it would be demolished to make way for Heinz Filed and PNC Park. This gave the city the stadiums Ritchey thought it should have had all along.

A Loved Man

In 1973 Dahl’s beloved wife Kay passed away. After a few years his staff thought it time for him to marry once again. Dahl had a love for sauerkraut. He announced that he would marry the woman who made the best sauerkraut. Many sauerkraut dinners from eligible ladies were served to him. Dahl then asked the head treasurer, of thirteen years, in his office if she made sauerkraut. Bea replied that she did. She must have made fabulous sauerkraut because they were married in 1976, three months later. They wed at St. Paul’s Cathedral in Oakland, PA.

Later Years

Dahl officially retired three years later in 1979. Together Dahl and Bea traveled all over the world looking for something new to discover. Dahl wasn’t interested in visiting a place if he didn’t feel that it had great architecture. When in Africa Dahl would draw sketches instead of take pictures. Those drawings graced the walls of his Bradford Woods home for many years. They were a reminder of a wonderful time in his life. He would often give away the drawings from his travels to friends and colleagues.

Dahl loved his community church. He had a big heart and donated land to the church for the minister’s house. The church also sponsored a Boy Scout troop that Dahl was a leader of. Dahl showed that you were never “too big” to give back to your community. The residents loved him in for his generous nature.

Dahl loved his community church. He had a big heart and donated land to the church for the minister’s house. The church also sponsored a Boy Scout troop that Dahl was a leader of. Dahl showed that you were never “too big” to give back to your community. The residents loved him in for his generous nature.

Dahl’s believed in treating everyone the same no matter how well known or well off hey were. He had friends all over the world. Once while waiting for a flight in an India airport he was spotted by someone he knew. It turned out to be the U.S. Ambassador to India. He crossed paths with Presidents Truman, Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson.

Dahl was honored by the American Institute of Architects in 1998 for his lifetime of architectural contributions. Dahl benefitted many young architects as a teacher at CMU, Harvard University, and Georgia Institute of Technology. He mentored others over his career spanning almost five decades.

In addition to the few buildings mentioned in this article he played a key role in designing many other buildings. Carnegie Mellon University houses the Ritchey Collection. It includes photographs, drawings, films, reports, renderings, slides, microforms, brochures, and clippings representing approximately 100 projects he participated in over his career.

After a lengthy illness Dahl Ritchey died on January 12, 2002. This was on his 26th wedding anniversary to Bea and just two weeks prior to his 92nd birthday. Despite being ill he never lost his positive outlook and cheerful disposition.

The contributions Dahlen K. Ritchey made to Pittsburgh are long lasting. The lives he touched continue today through a scholarship program set up at Carnegie Mellon University in his name. The buildings he designed that are still in use today are a constant reminder of his contributions to Pittsburgh. Even Dahl’s architectural firm continues as DRS Architects. The next time you enjoy a lunch-time concert in Mellon Square or move a college student into the towers at the University of Pittsburgh think of Dahlen K. Ritchey.

By Diane Gliozzi